|

Contents » Cover |

||

|

Reviews

Somewhat of a cross between Williams' Paterson, Olson's Maximus Poems, and Dante's Divine Comedy, Giscome Road is an exploration, by the ancestor of an explorer, of blood and water, family and names, and Afro-Caribbean heritage written mostly in long lines that mirror the content of these:

the name cycled along sourceless in the trees C. S. Giscombe's repeated tones bring us the news of the past and present, a new historical sense of this continent, where a man can lose a leg because of fucking two women, or an eye in a fight, and can taste blood as rich as strawberry juice. You too taste this "blood as if it were out there telling," let dark earth fill your mouth.

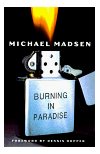

Madsen is at once a weary, jailhouse Bukowski and a street wizened Baudelaire. He examines the world around him with detachment that can be chilling and insight that slides easily into flesh, letting warm blood flow. His poems are like the artworks he sees in the Prado:

Faces, faces always passing, If some poets write poems that are raw instead of cooked, Madsen writes poems that are like a shot animal taking its last breath, the blood just beginning to color fur. He's a rough; he's got his finger in the wound.

In her collection, Myles includes her statement of poetics, "The Lesbian Poet." She writes how even though she is a lesbian, she has gained much from three male poets—"Jimmy Schuyler, John Wieners, and Robert Creeley." The first two are gay men, Schuyler one of the original New York Poets, Wieners a student of Duncan's and Olson's at Black Mountain. Creeley, in my view, is the most important poet of form since Williams. Myles also mentions Ginsberg, Stein, and half a page of women writers from every strain, including Kathy Acker, Marilyn Hacker, Barbara Guest, and Anne Waldman. Myles is proof of the axiom that to be avant garde one must be part of a movement. One must know the source of one's poetry and how a new poetry emerges from it. School of Fish is Myles' ninth book. It is a breakthrough book, one that should, as a result of its discussion of poetics and its stunning poetry, find an audience of younger women writers in particular but also any other bent and non-M.F.A. writing poet male or female. Mostly, her poetry resembles in appearance the short-lined poems of Creeley and Schuyler, and she is as contemplative as both, but she gains a flow of her own both in form and content:

I saw that Like Creeley, she's a brilliant poet of love, but a woman loving women love. Here is the poem "No No," which closes the book:

Look I don't know In those last five lines, what a payoff.

|

|||||||||||